Analog Instant in a Digital World

When the instant 20×24 format was created in 1976, it was a different world in photography. Fine art photography was still dominated by black and white, even though color was beginning to gain acceptance. Print sizes rarely exceeded 16×20 inches with 11×14 more the norm. Along comes this gargantuan machine containing its own processor that delivered 20×24 inch Polacolor images in 75 seconds. The quality was astounding, as the negative was the same size as the final print and there was no optical enlargement. There was lushness to the somewhat limited color palette and the diffusion transfer process rendered skin tones like Renaissance glaze painting. It was truly a remarkable process.

Fast forward thirty-five plus years and the photographic landscape has radically changed. Digital technologies grew in quality at a pace no one predicted and analog film lost favor first with the consumer market and eventually the professional market. The fine art market still holds on with established and even young artists embracing the attributes of analog. Contemporary professional DSLR cameras are capable of capturing a dynamic range that rivals medium and large format analog systems. Advances in the Camera Raw format and sophisticated image editors such as Lightroom and Aperture allow the photographer advantages in processing only the finest analog practitioners could achieve.

Still, the 20×24 instant format endures and is revered for all of its original attributes. It is also revered because it is not digital. All large format photography separates itself from digital in many ways; the size of the camera often means it is on a stationary tripod. Viewing the image is completely different, as one must view the image upside down on a ground glass and compose by shifting, rising, swinging and tilting the lens and film standards. As the composition is finalized, the lens is closed and a film holder inserted to take a singular image. A digital photographer could take a hundred different variations of the image while the large format photographer makes one. It is that discipline that separates these two photographic methodologies.

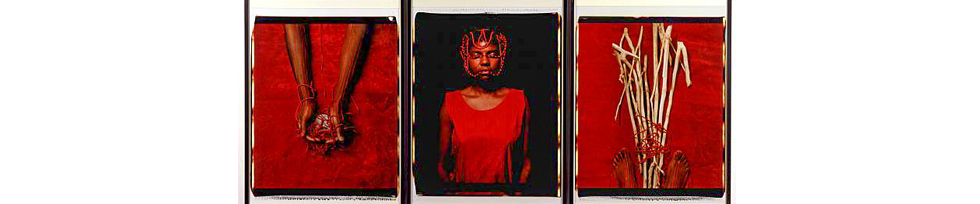

The 20×24 falls into its own category. Because of the size and complexity of the camera itself and the attending lighting system, it is run by a crew of at least two, with the photographer taking the role of director. It is a collaborative process, in some ways similar to film making but also to print making, as the final result will exit the camera in a matter of minutes. There is no post processing; all decisions of exposure, filtration, and processing time are decided on the spot. As the image is peeled and placed on the wall for viewing, everyone involved from the subject, photographer and crew is obviously aware of what has been achieved. While digital setups can show the image immediately on a large high-resolution monitor, it is not the same experience as experiencing the final print. The digital photographer will continue to shoot, perhaps long after they have achieved the best image, because it is simply easy to do so. With 20×24, because of its expense and deliberate approach, the photographer will recognize the best image, often with the input of their subject. While many photographers prefer this large format analog print as the end product, digital technology now allows for scanning to create stunning enlargements or editions from the analog original. This allows artists to expand their markets in ways that painters did in the 19th Century as printmaking became very popular.

Why not fake it, you might ask? A highly skilled digital artist could take a high-resolution digital capture from an 80mp digital back and try to simulate the optical characteristics of large format lenses, they could ramp back the color to simulate the more limited palette of color instant films, they could scan the unique edge marks that 20×24 cameras produce, they could hope to but never achieve the depth of a diffusion transfer print. They could do all these things, and perhaps fool a great many people. So can art forgers simulate a DaVinci or Picasso, and again one could fool a great many people and even experts for a time. Inevitably it comes down to authenticity and a 20×24 instant photograph is the epitome of authenticity.

It is especially so in 2012, thirty-six years after its invention.